14 KiB

Navigation

This module assumes you know how to launch termmines in Ghidra using GDB, and know where to find the basic Debugger GUI components.

It also assumes you are familiar with the concepts of breakpoints and machine state in Ghidra.

If not, please refer to the previous modules.

This module will address the following features in more depth:

- The Trace tabs — in the Dynamic Listing window

- The Threads window

- The Stack window

- The Time window

Coordinates

The term location is already established in Ghidra to refer to the current program and current address. There are more elements to a "location" in a dynamic session, so we add additional elements to form the concept of your current coordinates. All of these elements can affect the information displayed in other windows, especially those dealing with machine state.

- The current trace. A trace database is where all of the Debugger windows (except Connections and Terminal) gather their information. It is the analog of the program database, but for dynamic analysis.

- The current thread. A thread is a unit of execution, either a processor core or a platform-defined virtual thread. Each thread has its own register context. In Ghidra, this means each has its own instance of the processor specification's "register" space.

- The current frame.

A frame is a call record on the stack.

For example,

mainmay callgetc, which may in turn callread. If you wish to examine the state ofmain, you would navigate 2 frames up the stack. Because functions often save registers to the stack, the back-end debugger may "unwind" the stack and present the restored registers. - The current time. In general, time refers to the current snapshot. Whenever the target becomes suspended, Ghidra creates a snapshot in the current trace. If you wish to examine the machine state at a previous time, you would navigate to an earlier snapshot. "Time" may also include steps of emulation, but that is covered in the Emulation module.

In general, there is a window dedicated to navigating each element of your current coordinates.

If you do not have an active session already, launch termmines.

Trace Tabs

The Dynamic Listing window has a row of tabs at the very top. This is a list of open traces, i.e., of targets you are debugging. You can also open old traces to examine a target's machine state post mortem. In general, you should only have one trace open at a time, but there are use cases where you might have multiple. For example, you could debug both the client and server of a network application. To switch to another trace, single-click its tab.

When you switch traces, every Debugger window that depends on the current trace will update. That's every window except Connections and Terminal. (Each connection has its own Terminal windows.) The Breakpoints window may change slightly, depending on its configuration, because it is designed to present all breakpoints in the session.

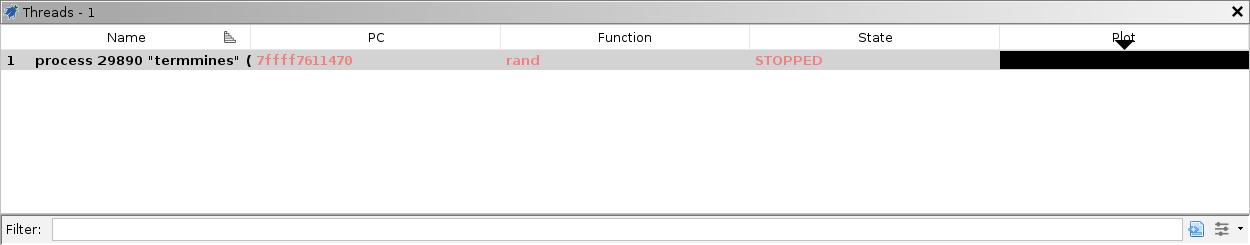

Threads

The Threads window displays a list of all threads ever observed in the target.

This includes threads which have been terminated.

Unfortunately, termmines is a single-threaded application, so you will only see one row.

If there were more, you could switch to a different thread by double-clicking it in the table.

The columns are:

- The Name column gives the name of the thread. This may include the back-end debugger's thread id, the target platform's system thread id, and/or the back-end debugger's display text for the thread.

- The PC column gives the program counter of the thread.

- The Function column gives the function from a mapped program database containing the program counter.

- The State column gives the state of the thread. This may be one of ALIVE, RUNNING, STOPPED, TERMINATED, or UNKNOWN.

- The Plot column plots the threads' life spans in a chart.

NOTE: Most of the time, switching threads will also change what thread is being controlled by the Control actions in the global toolbar.

This may vary subtly, depending on the action and the target.

For example, the  Resume button will usually allow all threads to execute; whereas the

Resume button will usually allow all threads to execute; whereas the  Step Into button will usually step only the current thread.

If the target's thread scheduler cannot schedule your current thread, the behavior is not clearly defined:

It may step a different thread, it may cause the target to block until the thread can be scheduled, or it may do something else.

Step Into button will usually step only the current thread.

If the target's thread scheduler cannot schedule your current thread, the behavior is not clearly defined:

It may step a different thread, it may cause the target to block until the thread can be scheduled, or it may do something else.

When you switch threads, everything that depends on the current thread may change, in particular the Stack window and any machine-state window that involves register values. The Registers window will display the values for the new thread, the Watches window will re-evaluate all expressions, and the Dynamic Listing and Memory views may seek to different addresses, depending on their location tracking configurations.

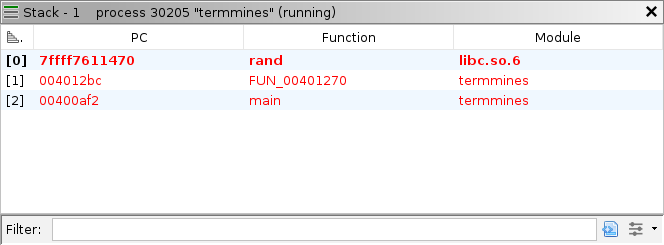

Stack

Ensure your breakpoint on rand is enabled, and resume until you hit it.

The stack window displays a list of all the frames for the current thread.

Each thread has its own execution stack, so the frame element is actually dependent on the thread element.

The call records are listed from innermost to outermost.

Here, main has called an unnamed function, which has in turn called rand.

The columns are:

- The Level column gives the frame number. This is the number of calls that must be unwound from the current machine state to reach the frame.

- The PC column gives the address of the next instruction in that frame. The PC of frame 0 is the value of the PC register. Then, the PC of frame 1 is the return address of frame 0, and so on.

- The Function column gives the name of the function containing the PC mapped to its static program database, if available.

- The Module column gives the name of the module containing the PC.

Double-click the row with the unnamed function (frame 1) to switch to it. When you switch frames, any machine-state window that involves register values may change. NOTE: Some back-end debuggers do not recover register values when unwinding stack frames. For those targets, some windows may display stale meaningless values in frames other than 0.

Exercise: Name the Function

Your Dynamic and Static Listings should now be in the unknown function. If you have not already done so, reverse engineer this function and give it a name.

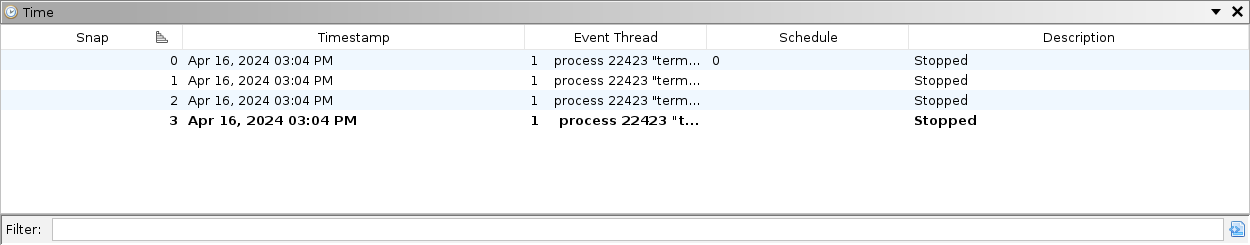

Time

Re-launch termmines, ensure both of your breakpoints at srand and rand are enabled, and resume until you hit rand, then step out.

Now, switch to the Time window.

It displays a list of all the snapshots for the current trace. In general, every pause generates a snapshot. By default, the most recent snapshot is at the bottom. The columns are:

- The Snap column numbers each snapshot. Other windows that indicate life spans refer to these numbers.

- The Timestamp column gives the time when the snapshot was created, i.e., the time when the event occurred.

- The Event Thread column indicates which thread caused the target to break. This only applies to snapshots that were created because of an event, which is most.

- The Schedule column describes the snapshot in relation to another. It typically only applies to emulator / scratch snapshots, which are covered later in this course.

- The Description column describes the event that generated the snapshot.

This can be edited in the table, or by pressing

CTRL-SHIFT-Nto mark interesting snapshots.

Before we can navigate back in time, you must change the Control Mode to Control Trace.

Now, switch to the snapshot where you hit srand (snapshot 1 in our screenshot) by double-clicking it in the table.

This will cause all the machine-state windows to update including the Stack window.

If you try navigating around the Dynamic Listing, you will likely find stale areas indicated by a grey background.

NOTE: The control-mode change is required to avoid confusion between recorded and live states. When you switch back to Control Target (with or without edits), the Debugger will navigate forward to the latest snapshot and prohibit navigating to the past.

Sparse vs. Full Snapshots

Regarding the stale areas: the Debugger cannot request the back-end debugger provide machine state from the past.

(Integration with timeless back-end debuggers is nascent.)

Remember, the trace is used as a cache, so it will only be populated with the pages and registers that you observed at the time.

Thus, most snapshots are sparse snapshots.

The most straightforward way to capture a full snapshot is the  Read Memory button with a broad selection in the Dynamic Listing.

We give the exact steps in the next heading.

To capture registers, ensure you navigate to each thread whose registers you want to capture.

Read Memory button with a broad selection in the Dynamic Listing.

We give the exact steps in the next heading.

To capture registers, ensure you navigate to each thread whose registers you want to capture.

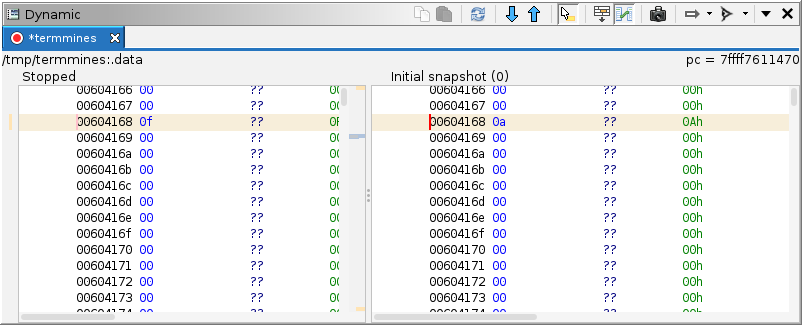

Comparing Snapshots

A common technique for finding the address of a variable is to take and compare snapshots. Ideally, the snapshots are taken when only the variable you are trying to locate has changed. Depending on the program, this is not always possible, but the technique can be repeated to rule out many false positives. The actual variable should show up in the difference every time.

For example, to find the variable that holds the number of mines, we can try to compare memory before and after parsing the command-line arguments. Because parsing happens before waiting for user input, we will need to launch (not attach) the target.

-

Launch

termmines -M 15in the Debugger. (See Getting Started to review launching with custom parameters.) -

Ensure your breakpoint at

srandis enabled. -

Use

CTRL-Ato Select All the addresses. -

Click the

Refresh button.

NOTE: It is normal for some errors to occur here.

We note a more surgical approach below.

Refresh button.

NOTE: It is normal for some errors to occur here.

We note a more surgical approach below. -

Wait a moment for the capture to finish.

-

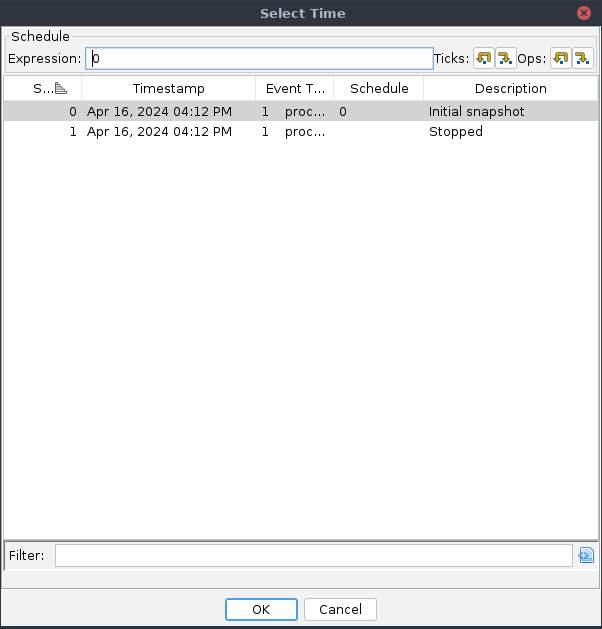

Optionally, press

CTRL-SHIFT-Nto rename the snapshot so you can easily identify it later, e.g., "Initial snapshot." Alternatively, edit the snapshot's Description from the table in the Time window. -

Capture another full snapshot using Select All and Refresh.

-

In the dialog, select the first snapshot you took.

-

Click OK.

The result is a side-by-side listing of the two snapshots with differences highlighted in orange. Unlike the Static program comparison tool, this only highlights differences in byte values. You can now use the Next and Previous Difference buttons in the Dynamic Listing to find the variable.

Notice that you see the command-line specified value 15 on the left, and the default value 10 on the right. This confirms we have very likely found the variable.

NOTE: Using Select All to create your snapshots can be a bit aggressive.

Instead, we might guess the variable is somewhere in the .data section and narrow our search.

For one, including so much memory increases the prevalence of false positives, not to mention the wasted time and disk space.

Second, many of the pages in the memory map are not actually committed, leading to tons of errors trying to capture them all.

Granted, there are use cases where a full snapshot is appropriate.

Some alternatives, which we will cover in the Memory Map module, allow you to zero in on the .data section:

- Use the Memory Map window (borrowed from the CodeBrowser) to navigate to the

.datasection. The Dynamic Listing will stay in sync and consequently capture the contents of the first page. This specimen has a small enough.datasection to fit in a single page, but that is generally not the case in practice. - If there are more pages, use the Regions window. Click the Select Rows then the Select Addresses buttons to expand the selection to the whole region containing the cursor.

Then click Read Memory in the Dynamic Listing.

This will capture the full

.datasection, no matter how many pages. - Alternatively, Use the Modules window to select

termminesand load its sections. (Not all debuggers support this.) Click the Show Sections Table button in the local toolbar to enable the lower pane. Use the Sections table to select the addresses in the.datasection, then click Read Memory in the Dynamic Listing. This will also capture the full.datasection.

Exercise: Find the Time

In termmines, unlike other Minesweeper clones, your score is not printed until you win.

Your goal is to achieve a remarkable score by patching a variable right before winning.

Considering it is a single-threaded application, take a moment to think about how your time might be measured.

TIP: Because you will need to play the game, you should enable Inferior TTY in the launcher.

Use the snapshot comparison method to locate the variable.

Then place an appropriate breakpoint, win the game, patch the variable, and score 0 seconds!

If you chose a poor breakpoint or have no breakpoint at all, you should still score better than 3 seconds. Once you know where the variable is, you can check its XRefs in the Static Listing and devise a better breakpoint. You have completed this exercise when you can reliably score 0 seconds for games you win.

NOTE: If you are following and/or adapting this course using a different specimen, the timing implementation and threading may be different, but the technique still works.